In the salt marshes of the Atlantic coast, a tiny criminal operates in broad daylight. This emerald-green sea slug doesn’t just eat algae—it performs microscopic surgery, stealing only the chloroplasts and using them as biological solar panels for up to ten months. Meet Elysia chlorotica, the world’s only solar-powered animal that has perfected nature’s most sophisticated theft.

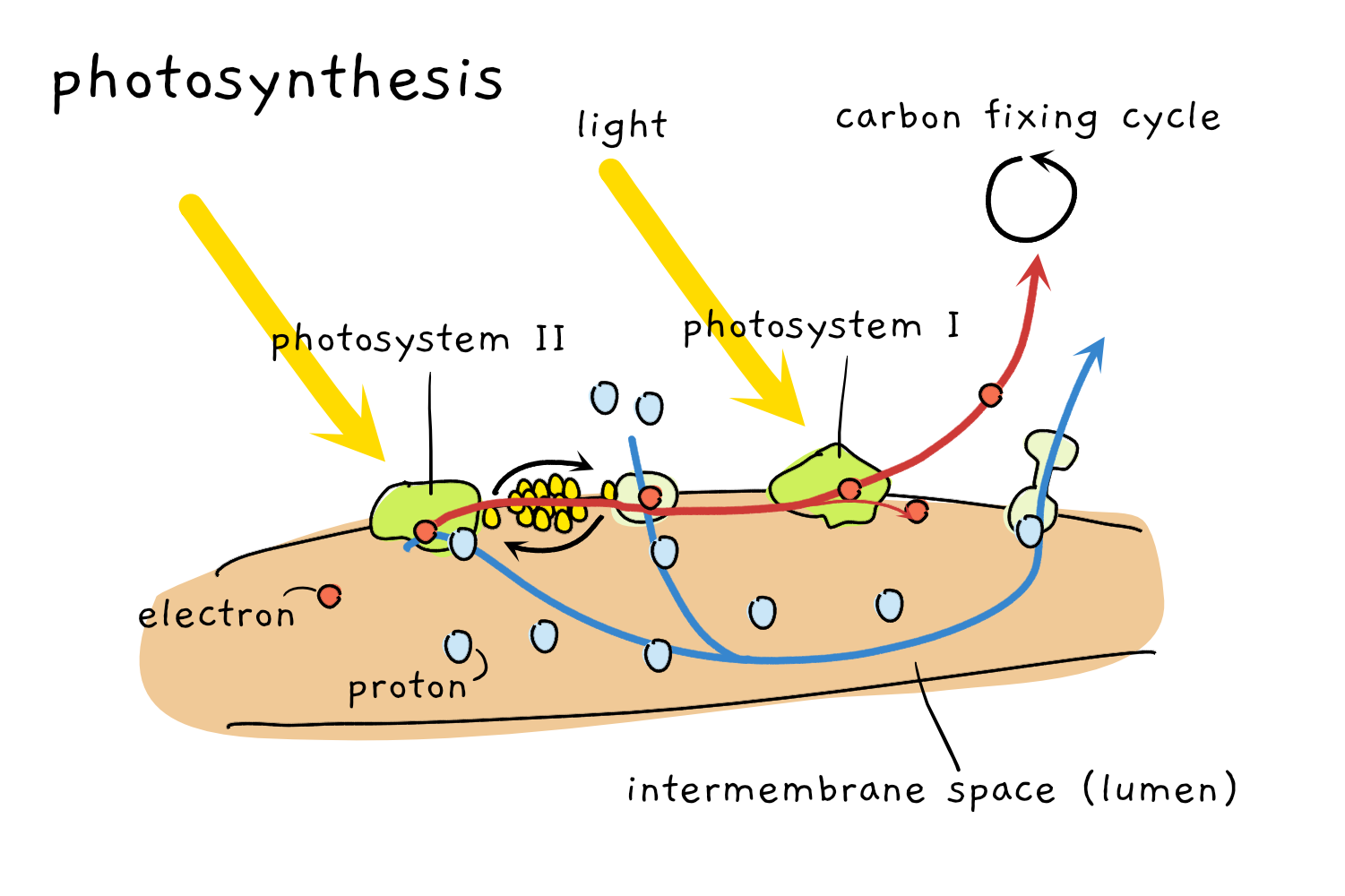

For over a century, biologists believed that photosynthesis—the process of converting sunlight into energy—was exclusively the domain of plants, algae, and certain bacteria. Animals, they thought, were forever destined to consume other organisms for energy. Then researchers discovered something that shattered this fundamental assumption: a sea slug that could photosynthesize using stolen plant machinery.

The Biological Heist: How Solar Theft Actually Works

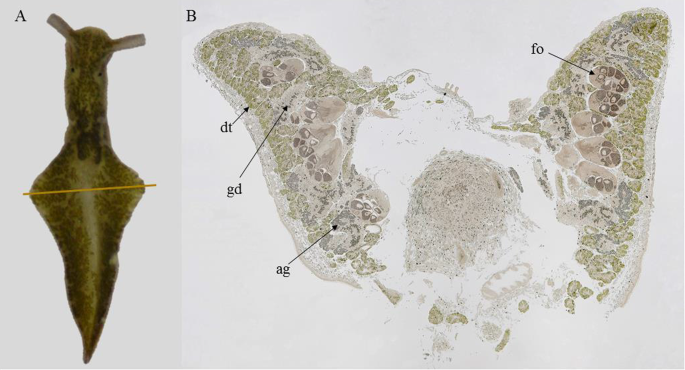

Elysia chlorotica doesn’t just happen upon its solar powers—it commits deliberate, calculated theft. When this remarkable mollusk encounters its preferred prey, the algae Vaucheria litorea, it uses a specialized feeding structure called a radula to pierce the algal cells with surgical precision.

But here’s where the story becomes extraordinary: instead of digesting the entire algae, the sea slug performs what can only be described as cellular surgery. It extracts only the chloroplasts—the green, photosynthetic organelles that function as nature’s solar panels—and leaves the rest behind.

These stolen chloroplasts are then transported through the slug’s digestive system and integrated into the cells lining its gut. Once there, they continue functioning exactly as they would inside a plant, converting sunlight into chemical energy through photosynthesis. The process is called kleptoplasty, literally meaning “stealing plastids,” and Elysia chlorotica has mastered it like no other creature on Earth.

The Ten-Month Solar Battery

What makes this biological crime even more astounding is its duration. While other kleptoplastic sea slugs can maintain stolen chloroplasts for days or weeks, Elysia chlorotica holds the world record: up to ten months of continuous photosynthesis using hijacked plant machinery.

To put this in perspective, some plants don’t even keep their own chloroplasts functional for this long. The sea slug has somehow solved one of biology’s greatest challenges—maintaining photosynthetic organelles without the genetic machinery that created them.

Recent research published in Royal Society Open Science confirmed this extraordinary retention period, tracking individual slugs through multiple seasons as they continued to derive energy from their stolen solar panels. The implications are staggering: an animal has essentially become a hybrid plant-animal organism while maintaining its animal DNA completely intact.

The Mystery of Maintenance Without Genes

For decades, scientists puzzled over a fundamental question: how does Elysia chlorotica maintain complex plant organelles without having plant genes? Chloroplasts require constant maintenance, repair proteins, and molecular support systems—all typically provided by the plant’s nuclear DNA.

The answer, it turns out, doesn’t involve genetic theft at all. Contrary to early theories about horizontal gene transfer, recent genomic studies have found no evidence that the sea slug incorporates algal genes into its own DNA. The slug remains genetically 100% animal, yet somehow keeps plant organelles alive for months.

The breakthrough came in 2025 when Harvard researchers discovered the mechanism: specialized cellular containers called “kleptosomes.” These unique organelles, found only in kleptoplastic sea slugs, act as protective chambers that house the stolen chloroplasts and provide them with the molecular support they need to survive.

As reported in the Harvard Gazette, these kleptosomes represent an entirely new form of cellular organization—a hybrid structure that bridges the gap between plant and animal biology.

A Living Solar Panel Farm

The practical implications of this biological solar theft are remarkable. Elysia chlorotica essentially transforms itself into a living solar panel farm, capable of generating energy from sunlight while still maintaining all its animal characteristics and behaviors.

During peak photosynthetic periods, these sea slugs can derive significant energy from their stolen chloroplasts. Studies using radioactive carbon dioxide have shown that the slugs actively fix carbon through photosynthesis, incorporating it into their cellular structures just like plants do.

However, the relationship isn’t perfectly efficient. Unlike true plants, Elysia chlorotica cannot survive solely on photosynthesis. The stolen chloroplasts provide supplemental energy, but the slug still requires periodic feeding to maintain its chloroplast stockpile and meet all its metabolic needs.

Where to Find Nature’s Solar Thief

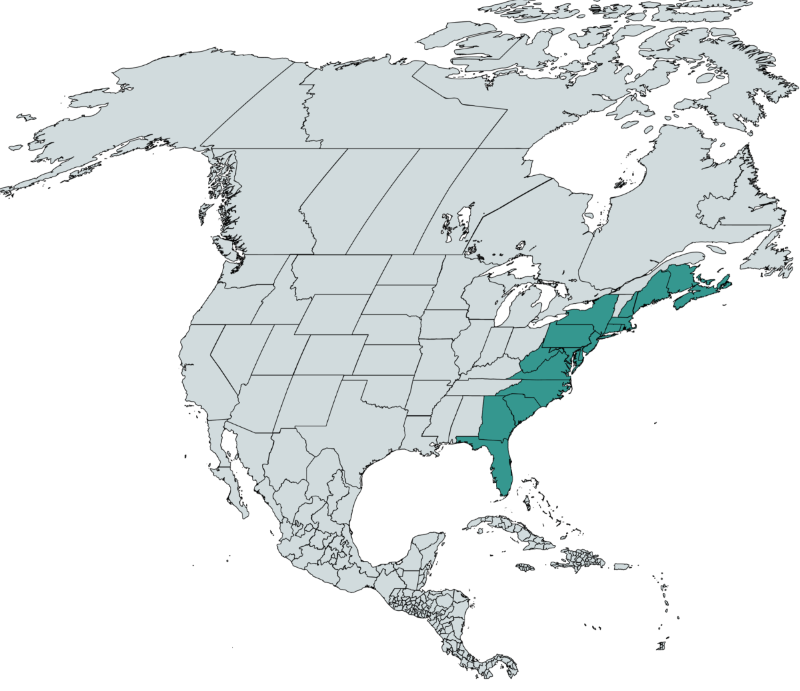

Elysia chlorotica inhabits shallow salt marshes and tidal creeks along the North American Atlantic coast, ranging from Nova Scotia down to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. Recent surveys have documented new populations as far south as Tampa Bay, Florida, suggesting the species may be expanding its range.

These emerald slugs are surprisingly small—typically measuring 20-30 millimeters in length, though some individuals can reach up to 60 millimeters. Their leaf-like appearance serves as perfect camouflage among the algae they hunt, making them nearly invisible to both predators and researchers.

The slugs show a strong preference for specific microhabitats: shallow areas with abundant Vaucheria litorea algae, gentle water movement, and sufficient sunlight to power their stolen photosynthetic machinery. They’re most active during daylight hours when their chloroplasts can maximize energy production.

The Evolution of Solar Theft

Elysia chlorotica belongs to a group of sea slugs called Sacoglossa, many of which practice some form of kleptoplasty. However, the retention times vary dramatically between species. While Elysia timida might keep chloroplasts functional for a few weeks, and Plakobranchus ocellatus for several months, E. chlorotica stands alone in its ten-month mastery.

This variation suggests that kleptoplasty evolved multiple times within the group, with different species developing different strategies for maintaining stolen organelles. The evolutionary pressure that drives this behavior is clear: in nutrient-poor marine environments, any additional energy source provides a significant survival advantage.

What remains mysterious is how E. chlorotica specifically evolved such sophisticated cellular machinery to support long-term kleptoplasty. The kleptosomes and associated molecular systems represent a remarkable evolutionary innovation—essentially, the development of entirely new organelles to house stolen ones.

Implications for Biotechnology and Medicine

The discovery of how Elysia chlorotica maintains stolen chloroplasts has profound implications beyond marine biology. Researchers are now exploring how these mechanisms might inspire revolutionary biotechnologies.

The concept of bio-hybrid systems—combining living biological components with engineered materials—has gained significant attention. If scientists could understand and replicate the slug’s kleptosome technology, it might become possible to create hybrid biological systems that combine the best features of plant and animal cells.

Potential applications include:

- Enhanced biofuels: Algae-animal hybrid systems that could be more efficient than traditional algae cultivation

- Medical devices: Bio-hybrid systems that could self-power using light, reducing the need for battery replacements

- Environmental monitoring: Self-sustaining biological sensors that operate indefinitely in sunlit environments

- Marine energy systems: Combining biological solar collection with innovative blue energy technologies for comprehensive renewable power solutions

- Space exploration: Life support systems that could generate oxygen and food using minimal resources

The research into kleptoplasty has also deepened our understanding of endosymbiosis—the process by which one organism lives inside another for mutual benefit. This knowledge could prove crucial for understanding how complex life evolved and how we might engineer beneficial partnerships between different types of organisms.

Debunking the Myths: What This Slug Can’t Do

Despite the remarkable nature of kleptoplasty, it’s important to address some common misconceptions about Elysia chlorotica:

Myth: It’s the first animal to photosynthesize Reality: Several animals, including corals and some jellyfish, photosynthesize through symbiotic relationships with algae. What makes E. chlorotica unique is that it steals and maintains plant organelles directly.

Myth: It becomes a plant Reality: The slug’s DNA remains completely animal. It simply borrows plant machinery temporarily.

Myth: It lives entirely on sunlight Reality: While photosynthesis provides significant energy, the slug still requires periodic feeding to survive and maintain its chloroplast supply.

Myth: It can photosynthesize indefinitely Reality: Even in E. chlorotica, stolen chloroplasts eventually degrade and must be replaced through feeding.

Conservation and Threats

While Elysia chlorotica is not currently listed as endangered, it faces significant conservation challenges. The species depends entirely on healthy salt marsh ecosystems and the presence of its specific algal prey, Vaucheria litorea.

Climate change poses multiple threats to these habitats:

- Sea level rise threatens coastal salt marshes

- Ocean acidification affects both the slugs and their algal prey

- Temperature changes could disrupt the delicate balance needed for successful kleptoplasty

- Coastal development continues to destroy critical habitat

The specialized nature of the slug’s lifestyle makes it particularly vulnerable to environmental changes. Unlike generalist species that can adapt to new food sources, E. chlorotica requires specific algae and optimal light conditions to maintain its remarkable photosynthetic abilities. This dependency on pristine marine environments echoes the challenges facing other innovative marine projects, such as Japan’s ambitious floating city developments that must also balance technological innovation with marine ecosystem preservation.

The Future of Solar-Powered Life

Recent advances in understanding kleptoplasty have opened exciting new research directions. Scientists are now investigating whether similar mechanisms might exist in other organisms, possibly overlooked due to their subtle nature.

The 2025 research from Harvard on kleptosomes represents just the beginning. Future studies will likely focus on:

- Molecular mechanisms: Understanding exactly how kleptosomes maintain chloroplasts

- Evolutionary origins: Tracing how kleptoplasty evolved in different species

- Bioengineering applications: Developing practical technologies inspired by these systems

- Conservation strategies: Protecting the unique ecosystems these creatures depend on

Lessons from Nature’s Master Thief

Elysia chlorotica challenges our fundamental understanding of the boundaries between plant and animal life. In an age where we’re developing increasingly sophisticated technologies, this tiny sea slug reminds us that nature has been solving complex engineering problems for millions of years.

The slug’s ability to steal, maintain, and utilize plant solar panels represents one of evolution’s most creative solutions to the challenge of survival in energy-poor environments. It demonstrates that the categories we use to organize life—plant, animal, photosynthetic, heterotrophic—are far more fluid than we once believed.

Perhaps most importantly, Elysia chlorotica shows us that some of nature’s most remarkable innovations are hiding in the most unexpected places. This unassuming sea slug, no bigger than a leaf, has mastered biological solar energy in ways that continue to inspire and baffle scientists.

As we face our own energy challenges and search for sustainable solutions, we might do well to pay attention to nature’s master thieves. The answers to some of our most pressing technological questions might already exist, perfected over millions of years of evolution, waiting to be discovered in a salt marsh or tide pool.

The next time you see a green leaf floating in coastal waters, look twice. It might just be nature’s most accomplished solar engineer, powered by the sun and perfecting the art of biological theft.

Research Tools and Resources We Use

In our mission to investigate and share fascinating discoveries like Elysia chlorotica, we rely on several specialized tools that help us access cutting-edge scientific research and communicate complex biological concepts effectively:

Secure Research Access: When diving deep into academic databases, international research institutions, and accessing restricted scientific papers about marine biology discoveries like kleptoplasty, we use Surfshark VPN to ensure secure connections to global research networks. This protection is essential when investigating emerging scientific breakthroughs and accessing peer-reviewed studies from institutions worldwide.

Scientific Visual Communication: Making complex biological processes like chloroplast theft and cellular integration understandable requires powerful visual storytelling. We use Pictory AI to transform intricate scientific concepts into engaging visual content, helping audiences grasp everything from microscopic cellular mechanisms to evolutionary processes that would otherwise remain abstract.

Science Newsletter Platform: Keeping our community of science enthusiasts updated on remarkable discoveries like solar-powered sea slugs and other biological mysteries requires reliable communication tools. We use Beehiiv to manage our science newsletter, ensuring subscribers receive timely updates about breakthrough research, conservation efforts, and the latest findings in marine biology and biotechnology.

These tools enable us to maintain the highest standards of scientific accuracy while making extraordinary biological discoveries accessible to curious minds everywhere, from casual nature enthusiasts to serious researchers exploring the frontiers of bio-hybrid technologies.